“There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot.” (Leopold 1968:xxi)

I have never lived alongside wild things, but this was not the case for Aldo Leopold.

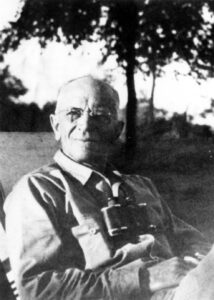

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) was an American forester, conservationist, and environmental philosopher whose work bridged science and ethics. He began his career as a U.S. Forest Service officer and eventually became a professor at the University of Wisconsin.

Leopold’s most enduring contribution came through his posthumously published work, “A Sand County Almanac” (1949), which articulated his land ethic philosophy and transformed how generations understood their connection to the natural world.

Leopold’s philosophy remains relevant today, in an epoch defined by human impact on Earth’s ecosystems. His call for an expanded ethical framework that includes the land itself offers crucial guidance for moving beyond the anthropocentric worldview that has dominated Western thought, proposing instead a biocentric approach that recognizes the intrinsic value of all components of the natural world.

The Early Life of Aldo Leopold

Courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation and University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives.

Born in Burlington, Iowa, in 1887, Aldo Leopold grew up in a family that valued outdoor pursuits. His father, an avid outdoorsman, instilled in young Aldo a deep appreciation for hunting, fishing, and natural observation.

From an early age, Leopold enjoyed observing birds and kept detailed journals of the birds he observed while walking in natural environments.

Leopold attended Yale Forest School, where he studied forestry. After graduating in 1909, he joined the U.S. Forest Service in Arizona and New Mexico. There, he participated in predator control programs, including killing wolves—experiences that would later lead to profound changes in his thinking about ecosystem integrity and predator-prey relationships.

What Is the Land Ethic?

Courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation and University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives.

The land ethic represents Leopold’s most significant philosophical contribution, expanding the boundaries of moral consideration to include entire ecological communities—the land itself.

Ethics typically concerns only human relations. It studies how we should act to maintain a harmonious community. Leopold’s land ethic also includes a biotic community composed of soils, waters, plants, animals, and their interconnections.

We tend to separate ourselves from nature and the environment. This framework suggests that humans are “plain members and citizens” of the biotic community, with corresponding responsibilities to the health and integrity of that community.

He writes: “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” (Leopold 1968: xxii) He encourages us to think of land as part of our community that we need to consider.

As a lifelong outdoor enthusiast, Leopold understood how beautiful and enriching the wilderness could be. In his famous maxim, he writes: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” (Leopold 1968:211)

This biocentric perspective doesn’t diminish human importance but places human welfare within a broader ecological context, recognizing that human health ultimately depends on ecosystem health.

How Leopold’s Ideas Transformed Conservation

Leopold’s land ethic transformed conservation from a utilitarian focus on resource management toward ethical stewardship. Prior to Leopold’s influence, conservation was guided by the principle of managing natural resources efficiently for human benefit. The land ethic introduced a framework recognizing the intrinsic value of natural systems and emphasizing moral obligations toward the broader biotic community.

The land ethic continues to influence contemporary sustainability movements, providing philosophical grounding for addressing climate change and biodiversity loss. Modern concepts like ecological economics and biomimicry reflect Leopold’s insight that human systems should work in harmony with natural systems rather than in opposition to them.

Critiques and Continuing Debates

Despite its influence, the land ethic faces significant criticisms. Leopold’s conservation movement was predominantly supported by white, male, and rural sportsmen, farmers, and foresters. Critics argue that his environmental ethic reflects only white and male perspectives, lacking inclusivity across different races, classes, and genders. While he may have been advanced in ecological thinking, he was still a man of his time. These issues of inclusivity may not have been prominent considerations during his lifetime.

Critics also argue that key terms like “integrity,” “stability,” and “beauty” are too vague for practical decision-making, and that deriving moral conclusions from ecological observations commits the naturalistic fallacy.

Conclusion

I was born and raised in a well-developed city, far from nature. I appreciate the comfort of city living, but I also want to learn more about the natural world.

Everything originates from the natural world: the food we eat daily, the clothes we wear, and the furniture we use all come from materials initially found in the natural environment.

I realize that without a rich and healthy natural environment, our comfortable lives would not be possible. Leopold’s philosophy serves as an important reminder that we need to conserve the land and its elements for a sustainable future.

Read books on him

Reference:

Leopold, Aldo. 1968. A Sand County Almanac: With Other Essays on Conservation from Round River. 2nd edition. With Charles W. Schwartz. Oxford University Press.

Meine, Curt. 2010. Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work. 3rd edition. Univ of Wisconsin Pr.